When you grow up among the rolling hills and weathered tors of the South West, landing a contract in Essex feels like you’ve been transported to a parallel geological dimension—one paved in concrete, dotted with shipping containers, and alarmingly rich in abandoned mattresses.

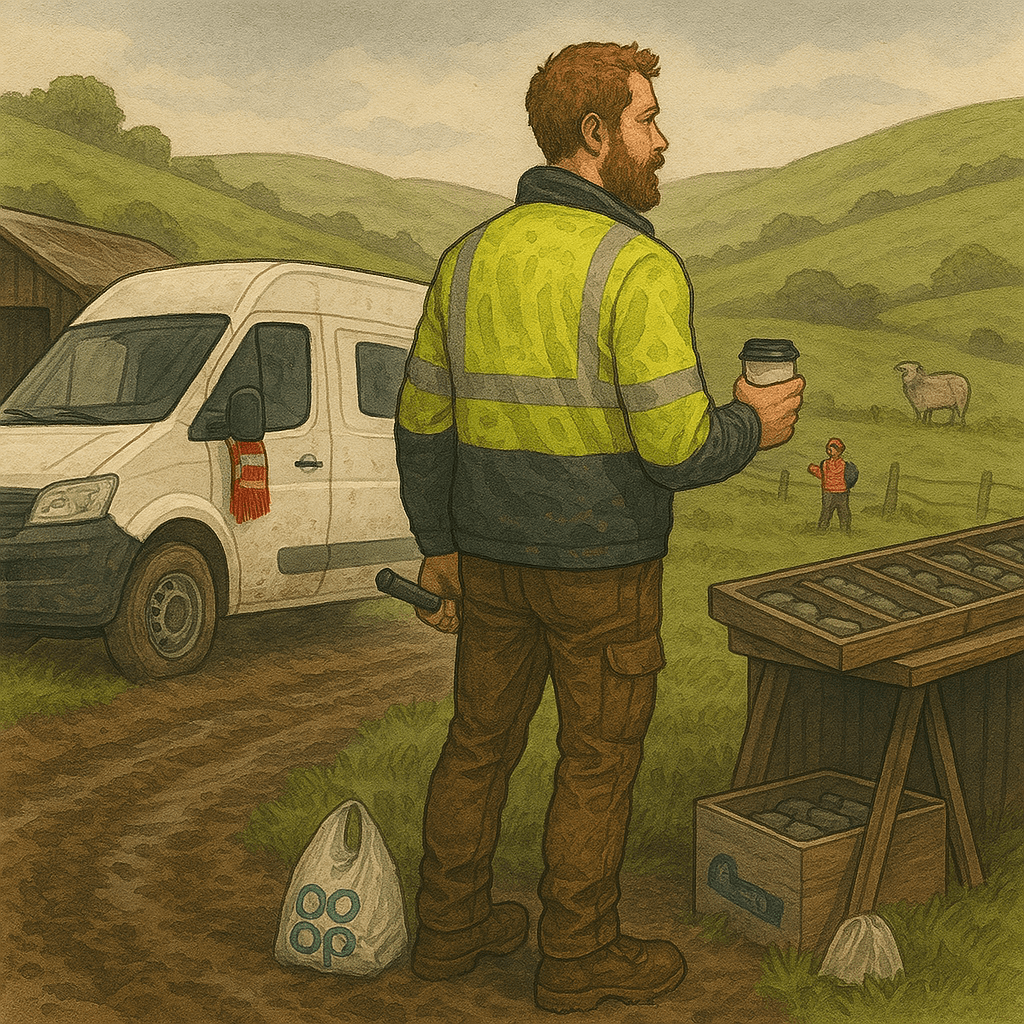

Yes, I’ve crossed county lines and now find myself deep in the industrial arteries of Essex. The campervan is my trusty base of operations, and I alternate between the relative luxury of campsites (with their glorious electric hook-ups) and the shadowy realm of stealth camping. There’s a certain thrill to whipping up dinner on a gas stove in a B&Q car park, with my air fryer buzzing quietly as it works its magic on some slightly questionable breaded chicken.

The geology here is not what I’m used to. Gone are the familiar sandstones and slates of the Westcountry. Instead, I’ve stepped into the world of contaminated land. My site is a strange patchwork of made ground, classed as BDA red—basically a polite way of saying “mystery fill, but definitely hazardous.” Beneath that, we’ve got some Alluvium, River Terrace Deposits, and the ever-reliable Lewes Nodular Chalk. There’s a decent bit of stratigraphy here… if you can get past the fridge dumped in the hedgerow.

The work is fascinating, and definitely outside my usual wheelhouse. I’ve been thrown into a technical speciality I’m not quite qualified for, so naturally, I’m spending evenings frantically Googling terminology and pretending I’ve known it all along. “Oh yes, definitely VOCs showing up in that groundwater plume… just as I suspected.” This might become a recurring theme—“Fake it ’til you make it: The Contaminated Chronicles.”

Despite the unusual setting, the team is brilliant—friendly, helpful, and good-humoured. They’ve made the adjustment smoother, and it’s been nice to be challenged in new ways. The weather’s been weirdly great too, which has made campervan life far more bearable. Long may it last.

When I’m not sleuthing for hydrocarbons or cooking off the tailgate, I’ve been seeking out local distractions. The cinema has become a regular haunt—even if the listings are somewhat tragic. I’ve now seen ‘A Complete Unknown’ four times. At this point, I’m not even sure if I like it or if it’s just become part of my Essex routine. Luckily, they did a rerun of The Big Lebowski the other week—a beacon of joy and chaos in a land of retail parks and skip fires. I’ll never tire of watching The Dude abide.

So here I am, the Nomadic Geologist, knee-deep in made ground and makeshift meals, forging a strange new rhythm in Essex. It’s not what I’m used to—but then again, that’s the point.

Until next time—stay curious, stay mobile, and always check for asbestos.

– The Nomadic Geologist